LOST CABIN: Unraveling the Mystery of the First Log Cabin in Kenosha, Wisconsin

PREFACE

The location of the first log cabin in Kenosha, Wisconsin, was firmly established when a historical marker was erected in 1976. Though no one knew the exact location where the cabin had stood in the early 1800s, its vicinity was recognized as the extreme northeast corner of Kenosha County. It is here that Jacob Montgomery, a local hunter, trapper, and trader, was known to have built his home in 1835. Most local historians were satisfied with those agreed-upon conclusions after years of conjecture and research by both professionals and hobbyists. Finding the cabin’s exact site, let alone a foundation or indications of footings, was not necessary to acknowledge the importance of the site in the history of the area.

I, however, was not in line with those who celebrated the marking of this historic site. Over the ensuing decades, I returned countless times to the subject, and after extensive research and exploration, have found myself in the position to compile and share what I have come to believe. This includes my firsthand recording of the archaeological evidence and more recent research in primary source materials, all of which confirm my findings.

Formation of the KAS

In 1974, I moved to Kenosha from southern Illinois, where I had been a member of the Central Wabash Archaeological Society. Naively, I assumed every county had an Archaeological Society. I was wrong. Surprisingly, Kenosha County never had one. Situated on Lake Michigan between Milwaukee and Chicago, the area has a rich history as the hunting grounds of the Paleo Indians. It was also the meeting place for trade and settlement from ancient times until now.

I discovered many people with deep interests in knowledge about these subjects and of the area. Coming to Wisconsin, I looked forward to continuing the type of archaeological research I had been doing in Illinois; Kenosha was to become a new adventure of forest and farmland to explore. Forming a new archaeological society here seemed to be a logical first step in gathering together people and resources to move forward in that request.

In 1974, I approached Dr. Kenneth Dearolf, who was the director and curator of the Kenosha Public Museum. Not surprisingly, he liked the idea of the society and suggested I contact Phil Sanders, who at the time was President of the Kenosha Historical Society. Again, it was no surprise that he was all for it. The three of us met a few days later at the museum and set a date for a second meeting which would be advertised to the public. If the turnout was small, it would indicate there was not enough local interest. If enough people showed up for the public meeting, we would move forward with plans to form an official group. As it turned out, a large crowd gathered, and an enthusiastic show of hands confirmed overwhelming interest. A new archaeological society was formed right then and there, and officials were voted in. Phil Sanders was elected President, and I became Chairman. I have no recollection of Dr. Dearolf’s position. Although he played a role in setting up the meeting to formulate the society, I do not recall him being prominent in the society afterward. KAS remains active today, some 45 years later.

My Early Works In Kenosha Co.

Two years into my exploration of the fields and byways of Kenosha County, I discovered and excavated a Native American burial which was being destroyed as a field was being plowed for cultivation. After receiving the landowners’ permission, I returned to the farm and excavated as a salvage operation, with the intent to take the remains to a safer location for reburial. What I discovered compelled me even more strongly to do just that. The site was in an area where the beach level was very early, and the burial was probably very ancient. The body had been interred on an old fossil beach facing Lake Michigan and the rising sun to the East. After I finished the task, I never disclosed to another soul where I laid that ancient person to rest.

Late that same year, I decided to try to find the site of a historic cabin attributed to Jacob Montgomery, an early settler of Wisconsin. No one had previously located where the cabin had once stood. I now knew the area within reasonable proximity. It was a wooded and cleared property next to an ancient trail which is now known as Green Bay Road. Green Bay Road had been an animal trail shared with indigenous people of the area long before the arrival of the white man and became an important trade route after. It went far south into Illinois and north into Michigan Territory, which is now partially known as Wisconsin. Michigan territory was also known as the Interior.

The trail pushed north from Illinois into the southeast corner of Wisconsin and acted as somewhat of a boundary between Somers and Kenosha Townships. The Ozanne House, a large frame house, was set in a small grassy area on the east side of the property. The house was over 100 years old and still being lived in. As luck would have it, a young man came out of the house while I was looking at the edge of the forest about 150 feet to the east. He came over to see what I was doing. He was friendly and talkative.

After we talked for a while, I told him I was looking for the Montgomery Cabin site, as it had been reported to be the first cabin built in Kenosha County. He led me back to the woods where I had originally been looking, pointed out a couple of sunken spots, and stated, “There used to be old cabins here but they were torn down many years ago”. He then left. I was excited, sure I had just been shown where the famous cabin had once stood. No other cabins had ever been mentioned to have been in this particular area before, so I had no reason to believe it was not the correct site.

The Montgomery Cabin has been a legend for over 100 years. The area was known by local historians but no one had ever considered looking for the cabin itself. For them, it was a fact and that was enough. They were satisfied to point in the general area. If they were correct then where did the cabin stand from 1835-1839? I was convinced I had found it. I reported my findings to the KAS, and we decided to attempt an excavation there to try to prove once and for all that I had indeed found the original Montgomery Cabin. Because the KAS was a fledgling organization at only 2 years old, we did not have the funds for a proper dig readily available.

Leaving the Society

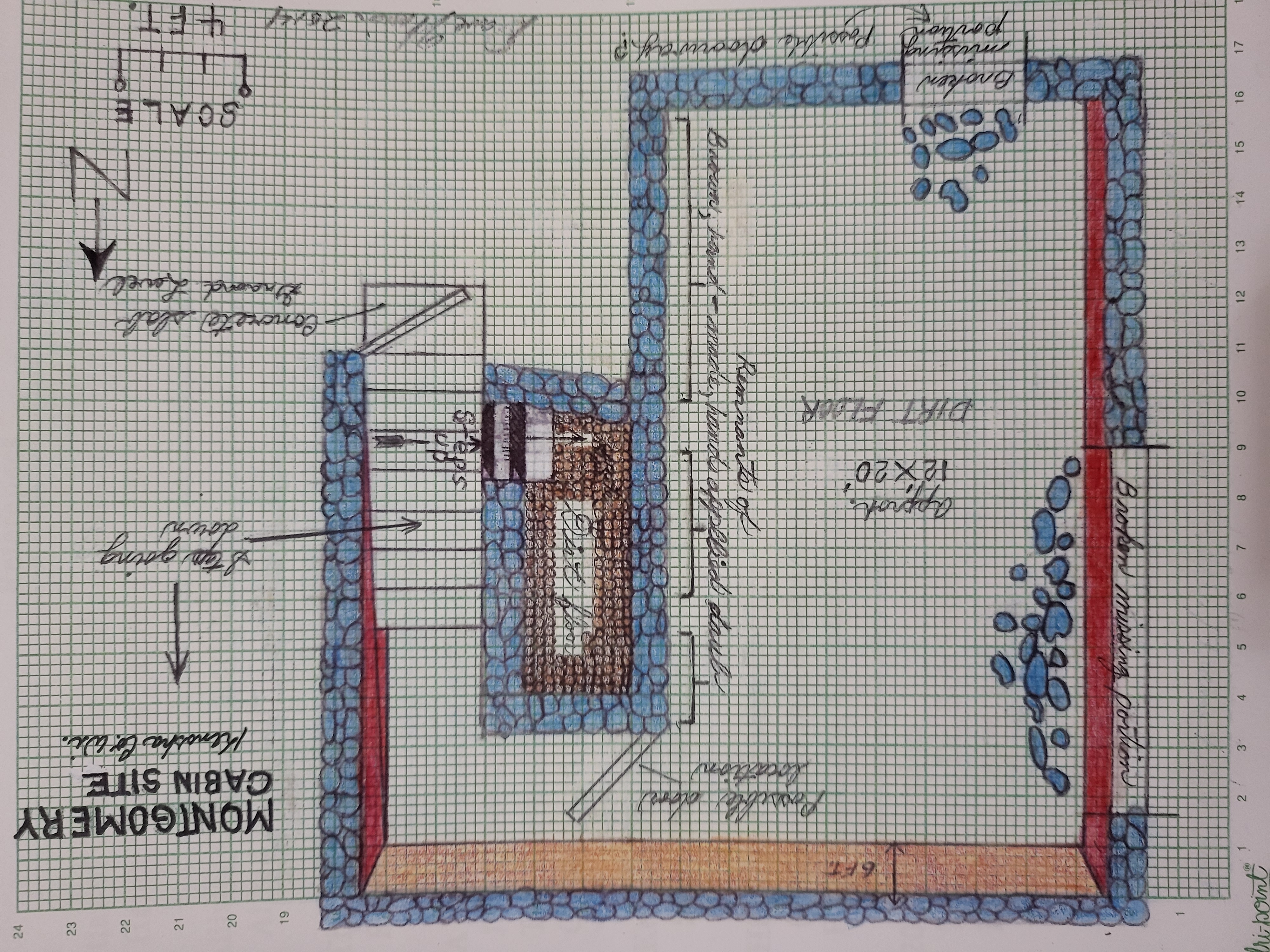

As fate would have it, the year we wanted to do the dig was 1976, the same year as the American Bicentennial celebrations. This allowed us to secure a $5,000.00 grant from the City of Kenosha along with their full cooperation for the dig. Since I had ram-rodded the society, I was put in charge of the operations. We laid out a N.S. grid covering the site area.

At first, everything went smoothly. We found pieces of pottery from the 1800s, a clay pipe, and even an arrowhead. A concentration of cobblestones began to appear that were reminiscent of a collapsed fireplace and chimney. It was looking more and more like we were uncovering the remnants of a historic cabin. One morning I reached the site before the other members had arrived. As I opened the fence gate and stepped inside, I was shocked.

The entire excavation site was in shambles. It looked as if wild pigs had destroyed all we had accomplished. It was obvious that looters had gotten in with hopes of finding treasure. I felt sick to my stomach. As the crew arrived they were all equally shocked. Finally, one of the members of the crew stated he knew who had done it. I was furious and wanted to know who so I could go to the local authorities to file a complaint and hopefully put a stop to it happening again. Once I realized he was not going to divulge any names, we ended up cleaning the mess and starting over. The vandalism took place on three occasions and I was at my wits end.

Eventually, one of the members decided to tell me what he knew. A Botany Professor from UW-Parkside was bringing his students over and plundering the site. Some of the older members of our group knew him but refused to confront him. They didn’t want to make waves simply because of his job title and seemed afraid of him. It was as if he did not want us to succeed for some unknown reason. I begged the society to confront him or at the very least, arrange it so that I could. They refused. My pleas fell on deaf ears. The vandalism stopped for a while and I thought it might be over.

I responded by stating that he had no clue at what he was doing or any training in archeology. Just because he was a Professor gave him no right to plunder a historical excavation. He was a bully and what he was doing was disgustingly unprecedented and intentional. He knew what he was doing but just did not care.

The Final Straw

One morning I came in early again only to find that the Botany Bunch had returned and tore up the site yet again. This was the last straw. When the rest of the crew arrived and saw what had happened, per usual they just wanted to overlook it. They were still afraid of an arrogant, spiteful, bully of a man just because he had a title in front of his name. At this point, I simply said, “I quit! I am out of the Society!” I got in my car, drove away, and never looked back.

The Cover-Up

Within a week the KAS had the whole site filled in with dirt and a large rock placed there. Inset into the rock was a bronze plaque informing all passersby that this was the site of the original Montgomery Cabin. The stone marker remains there as of today. To save face they made a bold statement without one iota of proof whatsoever that the short dig performed proved that it was the fabled Montgomery site. It was merely an assertion and a very weak one at that. To understand the significance of the Montgomery Cabin and its significance to Kenosha County, we would have to look at the history of the area before and after 1835. In 1829 Jackson had just won his second term as President of the USA. His official inauguration took place at the capitol in 1830. He planned to move all of the Indians east of the Mississippi River across into the Western Plains. Removal included Potawatomi in what is now southeastern Wisconsin and all of the Indians in the Michigan Territory. In 1833 the Indians in the area were forced to surrender their ancestral lands to the US Government. This was not strictly enforced until 1838.

1838 would later become a pivotal year for the Indians.

Jackson needed to find a trail that went all the way from Fort Dearborn in Chicago, north to Fort Howard in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Just such a trail was discovered along the western shore of Lake Michigan which had become known as the Green Bay Trail. Jacob Montgomery’s cabin had been built right next to the eastern side of the trail in what at the time was the extreme southeast corner of Somers Township in Kenosha County. Trouble for the Potawatomi started as early as 1830, three years before they were forced to cede their land. A vanguard of European settlers was already arriving, driving herds of cattle into southern Michigan territory. There is no reason not to believe this area was not affected by this European push. Today’s Wisconsin was a large part of the Michigan territory in 1830. Trails were scattered and numerous in Wisconsin. Many had been widened and turned into roads throughout Ohio, Illinois, and elsewhere. Other areas had been granted statehood early on. Wisconsin did not become a State until the spring of 1848. Nevertheless, between 1840 and 1850, Wisconsin’s non-Indian population went from 305,091 to 775,881. The population growth started after the Indian removal, around 1840.

In 1830 Jackson convinced Congress to create a road from Fort Dearborn to Fort Howard and surveying began at once. Having found the trail he needed, it was decided to turn the Green Bay Trail into a trace (road). The precedent at the time involved surveyors following section lines. To widen a trail into a road, the Government would possess a mile-wide section along the side of the trail and section it off for sale to finance the construction. Green Bay Road was very important in Wisconsin. It enabled the early settlers to transport their families, livestock, and possessions to start new lives on the frontier By 1832, Kenosha, Somers, and Racine Townships along the trail had been surveyed so that the road could be established.

The old Indian trail must have been rough as it was millennia old, most likely created by Bison. Travel was slow at best. The age of the Green Bay Trail can be attested to by a particular pre-historical Indian location known as the Barnes Creek Site, which lies east of the trail, close to the western shore of Lake Michigan. Some of my finds were numerous bison bones (which were mapped) as well as a bison headdress with several holes drilled beneath the horn core that was ou still placenta attached to a portion of the skull cap. For many years, pottery, bone tools, and numerous arrowheads were found on the site by local collectors. The type of artifacts taken off the site ranged from the Paleolithic to the time of first contact with Europeans. This covers around 10,000 years. Bison were probably quite numerous in the far eastern side of Wisconsin throughout that time. The last known specimen was killed in the 1840s by the grandfather of John Malls on his farm in the Kettle Moraine area.

In 1830, the same year President Jackson began opening the Green Bay Trail, he had plans to incite the removal of all Indians east of the Mississippi, as mentioned earlier. The white men to the south who manned the posts were the US Army. They gave assurances that the Indians’ rights to their land were absolute but those lands kept shrinking as the white settlers moved westward When settlers came down to the flatlands west of the Appalachian Mountains and down the Mississippi Delta, they knew what they wanted their west to look like. “An empire of cotton, not an Indian campground”. In 1830, the great cotton states of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia outlawed tribal kingdoms. President Jackson pushed a bill through Congress ordering all of the tribes, farmers or hunters, peaceful or hostile, to move west of the Mississippi.

The Choctaws, Creeks, and Chickasaws began to move. There was a brave pause while the Cherokee appealed to the Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Marshall upheld their claim that there was no constitutional right to remove them from their ancestral lands. Jackson called this decision, “too preposterous” In 1837, the last year of his second term as President, in one of the most shameless and arbitrary acts of any President, Jackson ignored the Supreme Court’s decision and ordered the Army to “get them out”. Martin Van Buren, the next President and with Jackson’s administration behind him, sent General Winfield Scott and 7,000 soldiers to Georgia with orders to expel the Cherokee. They were to be transported to the newly established Indian Territory in Oklahoma.

It was a savage and morbid exhibition by the soldiers. Not all of the soldiers’ hearts were in it. One sickened by his task reported, “I saw helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes and driven by bayonet into stockades in the chill rain. I saw them loaded like cattle and sheep onto wagons and they started towards the west”. This horrible trek to Oklahoma became known among the Cherokee as the “Trail of Tears” This forced journey took a tragic toll. Many fell ill and thousands died from exposure, diseases, and starvation. Those who died were buried in unmarked graves. 30,000 Cherokees were taken on that march with a third of them dying. The white Americans justified their atrocities and illegal land grabbing with a sick delusion of self-justification. Stating they must fulfill their, “Manifest Destiny” as granted by “Providence” to develop the continent Jackson and Van Buren targeted the 5 civilized tribes and eventually removed some 60,000 Native Americans from the Michigan Territory. This was accomplished under the guise of an “American ethnic cleansing”.

Although the Potawatomi had ceded their land in 1833 they still got along with the Europeans in the Michigan Territory. With the heavy push of whites entering the area by 1830, it brought along diseases that the Indians had little to no defense from. An epidemic broke out in Kenosha among the Potawatomi in 1832. It moved from the Illinois state line, north along the shores of Lake Michigan to Milwaukee and beyond. On June 10th, 1832 an epidemic of Asian cholera broke out in Chicago and spread north to Milwaukee along the Lake Michigan shoreline. 16 percent of white settlers died compared to one-third 12 of the Indian population. A Potawatomi village existed at the mouth of the Pike River in Kenosha County in the exact spot where a few years later, European settlers built cabins in hopes of starting a town. Later they moved to the south side of the river and established what we now know as the City of Kenosha.

That same year the Potawatami had another village at the headwaters of the same river. In 1832 a marker was erected just inside the gate of what is now known as Hawthorn Hollow which reads: Pioneer Road Chicago to Green Bay Established by the Federal Government 1832 A second marker was placed further north of Hawthorn Hollow near the county line. While the surveyors were mapping this area they finished their basic survey probably around 1834. They produced a map of the county surveyed up to 1835. Interestingly, Jacob Montgomery’s cabin was not on the survey map. They surveyed in 1832 and some cabins were

According to old records, there were settlers as early as 1830. In Bristol Township, Kenosha County alone, documents record a Reverend Ira Bristol, Mr. Levi Grant, Ethridge Wilber, Mr. Tuttle, and Mr. Joel Walker. Mr. Joel Waker made his claim in 1830 which then became Walkers Prairie Pleasant Prairie was settled in by Henry Miller, on June 4th,1833. The first permanent settlement in the Trevor, Wisconsin area in Kenosha County, was established on November 4th,1804. Another family name in the records is Mr. Fletch. Records state that he came with a small group that included Mr. Sriffon, Mr. Willard Stevens, A. Shwart, Allen Bond, Miller, and Deacon Cephas Weed. There is no record of who finished their cabin first. 14 The only record of Jacob Montgomery’s cabin being the first is in an 1876 speech by Mr. Simmons. This proved to be erroneous at least in that respect. Jacob Montgomery lived there from 1835-1840. It may have even been a little later into the early 40’s. Jackson did not push the Potawatomi tribe off of their land all at once after they ceded it in 1833. Many lived peacefully with the whites for an additional 5 years. In 1838, the same year the Cherokee were forcibly removed to Georgia to the Oklahoma Territory, US Army troops arrived in Milwaukee with wagons and supplies and the last vestige of relative freedom for the Potawatami was suddenly brought to an end. It’s a known fact that the earliest European settlers who lived off the land made little effort to upgrade their dwellings or attempted to farm and often took Indian wives. This is exactly the way Montgomery lived. He was a famous hunter but by no means is there evidence he attempted to farm or clear the forest. None whatsoever. O1d records state that he lived in his cabin for about 8 years. He simply vanished one day without a word and left no records behind of relatives. No one knows what happened to him. This means he left the area at about the same time the last Potawatami were pried from the area. The exact time the last of the Potawatomi disappeared in 1840, Jacob Montgomery vanished. Coincidence?

**After Montgomery Disappeared Montgomery disappeared sometime between 1838 and the early 1840’s depending on who you talk to but probably around 1840. Sometime between 1840 and 1855? Fred Ozanne built a frame house in the exact spot where the Montgomery Cabin stood. In Heilt his home was right on top of the cobblestone foundation that Montgomery had used. In the Fourth of July speech made by H.M. Simmons in 1876 he, said, “This cabin, almost exactly where the Montgomery cabin stood for 8 years”. People tend to glaze over this statement because the Ozanne house was still standing in 2013. In 1855 M Coonley built a cabin for his family in the extreme southeast corner of Somers Township. 150 feet east of where Montgomery’s cabin and Ozanne’s home stood. He lived there for 16 years until 1870.I believe that it has been made abundantly clear that the Montgomery cabin was NOT the first to be built in Kenosha County. 100 years later the Kenosha Archeological Society excavated “what they thought” was the original Montgomery cabin site when in fact they were in the wrong place. The beginning of this paper explains their work in some detail. The KAS’s cover uup worked for 37 years 16 The stone with the inscription sat in the same spot, deceiving anyone who stopped long enough to read it. Many people who located the 1976 marker felt pride in a myth that had morphed into fact, while it was little more than a supposition. In 1976 the KAS were convinced they were excavating the correct cabin and making hihistoryEnthusiasm and excitement were high. Sadly the excavation was never completed and no evidence was found connecting the dig site to the original Montgomery site. Fighting plunderers and a 1alackf experience in excavating were major contributors to its failure. This cover-up made the Society make things worse. Their claim has not been challenged for 37 years. 17 In 2013, Dan Joyce, now the retired director of the Kenosha Public Museums turned up with Dr. Sasso. Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside, to solve the Montgomery riddle once and for all. Working off the assumption that I had found the site in 1976, they asked if I would show them exactly where I thought it was and where we had excavated. I was more than happy to oblige. Finally, after all of these years two men with professional backgrounds had taken an interest to the point of doing their itigation After showing them where the KAS had dug, I was surprised to find they had opened their excavation on the exact spot we had some 37 years prior. After the old dig had been filled in with debris from the numerous vandalisms by the UW-Parkside Botany Professor, clean-ups starting over multiple times there was no verifiable stratigraphy needed to make sense of the whole operation. Why were they digging in the same spot? Why not near or near it, where they could get good, undisturbed results? Bottomline: They were working off of an old assumption that had been around for almost 40 years. They were going to “prove” what we had assumed in 1976. If that were not the case then why dig right on top of where the earlier dig had taken place? Unbelievably, with their credentials, expertise, and backgrounds they were excavating through plundered backfill. All they found was probably a cabin site but they had no idea who it had belonged it. In actuality, they were digging where the Coonly cabin had stood in 1855, a good distance from where

References:

- Taylor, Helen Hornbeck. Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History. Publisher, Year.

- Cooke, Allister. Allister Cooke’s America. Alfred A. Knopf, Year.

- The Story of America. Reader’s Digest Association Inc., Year.

- Greenberg, Joel. A Natural History of the Chicago Region. The University of Chicago Press, Year.

- Wasion, Dave. Kenosha Archeological Society Story. Year.

- Simmons, H.M. History of Kenosha County (Pioneer Life In Kenosha County). Chapter 1, 1876.

- Joyce, Dan, Dr. Bob Sasso. 2013 Excavation. Year.

- Highland Park Historical Society Facebook Podcast. “The Archeology of Two 19th Century Cabins in Kenosha,” May 20, 2019.

- History of Racine and Kenosha Counties. N.R. Alle, Transcribed by Angie Lietzau.

- Wasion, David. Resume. Address: 979 Wood Road, Apt. 208, Kenosha, WI, 53144. Phone: 262-595-0113.

Archaeological Work:

- Chesrow Site Excavation, Kenosha County, WI, 1998. Great Lakes Archaeological Research Center (GLARC).

- Hebior Mammoth Excavation, Kenosha County, WI, 1994. Field Supervisor, lithic and mapping illustrator.

- Lucas Site (Paleoindian campsite) Excavation, Kenosha County, WI, 1993. Field Supervisor, lithic and mapping illustrator.

- Schaefer Mammoth Excavation, Kenosha County, WI, 1992. Field Archaeologist, lithic, and mapping illustrator.

- Delevan Site Excavations, Walworth County, WI, 1979. GLARC; field excavator.

- Henschel Site Excavation, Sheboygan County, WI. GLARC; field excavator.

Site Testing Programs:

- Price Mastodon Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1994.

- Kniper Mammoth Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1994.

- Hebior Mammoth Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1994.

Area Surveys:

- Megafauna Site Mapping Project, Kenosha County, WI, 1994. Devised and illustrated a series of regional maps of known megafauna remains.

- Des Plaines River, Kenosha, WI, 1994. Independently surveyed east bank, located and mapped prehistoric sites.

- Silver Lake, WI, 1982-1983, 1994. Independently conducted field survey, discovered large burial mound.

- Paleo Beach, Kenosha, WI, 1994. Independently conducted field survey, located prehistoric sites.

- Pleasant Prairie Paleoindian Survey, Kenosha County, WI, 1990-92. The regional survey noted megafauna and Paleoindian sites.

- Pike River Survey, Kenosha County, WI, 1976-79, 1990-91. Independently conducted field survey.

- George Lake Survey, Kenosha County, WI, 1980-81 and 1991. Independently conducted field surveys and mapped sites.

- WisPark Survey, Kenosha County, WI, 1988. Local expert consultant and field surveyor for GLARC.

- Pike Creek Survey, Kenosha County, WI, 1987-88. Independently conducted archival research and field survey of sites.

- Deep Lake and Crooked Lake Surveys, Lake County, IL, 1982-83. Independently conducted field surveys and mapped sites.

- Toleston Ridge Survey, Kenosha County, WI, 1979-80. Independently conducted field survey.

- Des Plaines River Basin Survey, Kenosha County, WI, 1972-75. Independently conducted field survey.

Prehistoric Site Surveys:

- Mud Lake, Fenske, and Shaefer Megafauna Sites, Kenosha County, WI, 1992-Present. Independently performed archival and field research.

- Thomas Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1977-Present. Independently studied, identified, photographed, and cataloged artifacts.

- Copper Burial Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1994. Independently conducted initial field investigation.

- Henn Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1977-1994. Independently studied and identified the Henn collection of over 2,000 artifacts.

- Pederson Site, Big Bend, WI, 1978-79, 1992. Assisted in the excavation of bundle burial.

- Scott Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1991-92. Surveyed and mapped site, geomorphology, flora, and artifact distribution.

- Pike River Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1989-91. Independently discovered, surveyed, mapped, and reported Pike River Site.

- Barnes Creek Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1973-1989. Independently surveyed, mapped, and performed test excavations.

- Wolf Creek Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1984, 1986, 1988. Independently surveyed, mapped, performed test excavations, and reported the site.

- Ranch Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1984-85. Independently surveyed, mapped, and reported sites.

- Sand Ridge Site, Lawrenceville, IN, 1970-71, 1976-1978. Independently conducted field survey and excavated site.

- Parkside Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1976. Discovered and excavated archaic burial.

- Chesrow Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1972-76. Discovered, named, and identified Paleoindian habitation site.

- Krans Site, Kenosha County, WI, 1972-75. Independently surveyed, mapped, and performed test excavations.

Field School Teaching Experience:

- Assistant Supervisor, Marquette University Field School, Hebior Mammoth Site, 1994. Taught testing, grid layout, excavation, mapping, faunal and lithic identification.

- Assistant Supervisor, Marquette University Field School, Lucas Site, 1993. Taught testing, grid layout, excavation, mapping, and lithic identification.

Museum Work:

- Lake County Museum, Lake County, IL, 1979. Identification of historic and prehistoric artifacts.

- Kenosha Public Museum, Kenosha, WI, 1989. Identification of prehistoric projectile points. Archival research of archaeological sites.

- Kenosha County Historical Society Museum, Kenosha, WI, 1974. Design of Middle Woodland Hearth display.

Publications:

- “Cultural Contexts of